Credit: Don Loarie

Common Sharp-tailed Snake

Contia tenuis

Description

Listen to the Indigenous words for “snake” here!

Similar Species

The Western Yellow-bellied Racer may superficially resemble the Sharp-tailed Snake as they all have a uniform dorsal colour and lack patterning. However, the Western Yellow-bellied Racer is light greenish-grey with a bright yellow belly, and the juveniles have substantial patterning. In its range, the Sharp-tailed Snake is often confused with juvenile gartersnakes, particularly the Northwestern Gartersnake.

Common Sharp-tailed Snake

Western Yellow-bellied Racer

Northwestern Gartersnake (Juvenile)

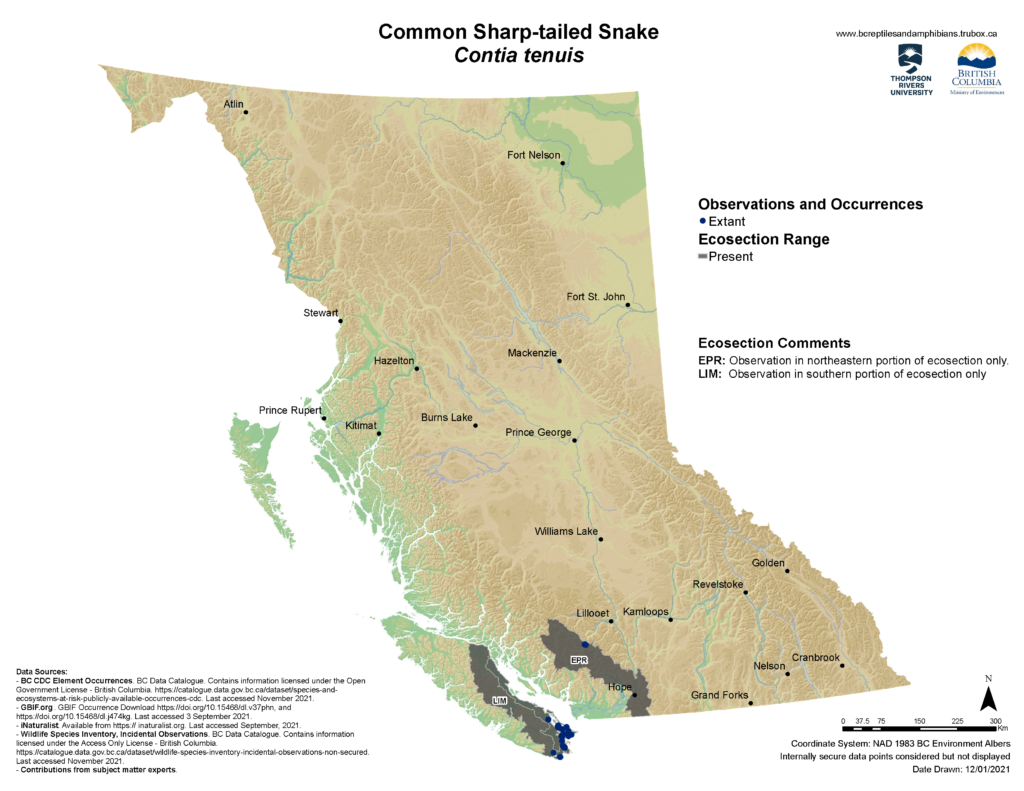

Distribution

Habitat

Reproduction

Mating in Common Sharp-tailed Snakes is thought to occur in the spring in British Columbia, when groups of male-female pairs can be encountered. Common Sharp-tailed Snakes are oviparousDefinition:A reproductive strategy where the female lays eggs that develop outside of the mother’s body., and lay 3 – 5 eggs in early summer in communal nesting sites, often in rocky crevices, underground, or in grass root clumps. Hatching occurs in the early autumn and juveniles develop very quickly. The age of sexual maturity is unknown but is likely reached between 3-6 years or at 20 cm in body length. Mark-recapture studies in British Columbia suggest that the lifespan of these snakes may be up to 9 years or more.

Diet

Conservation Status

Global: G5 (2016)

COSEWIC: E

SARA:1-E (2003)

Provincial: S1S2 (2018)

BC List: Red

Learn more about conservation status rankings here

Threats

Very little is known about the habitat use and behaviour of Common Sharp-tailed Snakes in British Columbia. If you see a Sharp-tailed Snake, report your observation to the Ministry of Environment and Climate Change.

Did You Know?

Common Sharp-tailed Snakes behave more like an amphibian than a reptile. During the heat of the summer, they are mostly inactive and may estivateDefinition:To spend a hot, dry season in an inactive, dormant state. Particularly in certain reptiles, snails, insects, and small mammals. underground until cooler weather.

Species Account Author: Marcus Atkins

B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2010. Species Summary: Contia tenuis. B.C. Minist. of Environment. Available: https://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/ (accessed Jun 16, 2021).

B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2018. Conservation Status Report: Contia tenuis. B.C. Minist. of Environment. Available: https://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/ (accessed Jun 16, 2021).

B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2021. BC Species and Ecosystems Explorer. B.C. Minist. of Environ. Victoria, B.C. Available: https://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/ (accessed Jun 16, 2021).

B.C. Ministry of Environment. 2006. Sharp-Tailed Snake Identification Guide. 2pp.

B.C. Ministry of Environment. 2015k. Recovery plan for the Sharp-Tailed Snake (Contia tenuis) in British Columbia. Prepared for the B.C. Ministry of Environment, Victoria, BC. 42 pp.

British Columbia Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection. 2002. Sharp-Tailed Snake Contia tenuis. British Columbia’s Wildlife at Risk Fact Sheet. 2pp.

COSEWIC. 2009e. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Sharp-Tailed Snake Contia tenuis in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vii + 38 pp. www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm).

Engelstoft, C., and K. Ovaska. 2000. Natural History of the Sharp-Tailed Snake, Contia tenuis, on the Gulf Islands, British Columbia. Pp. 293-294 in L.M. Darling, ed. 2000. Proc. Conf. on the Biology and Manage. Species and Habitats at Risk, Kamloops, B.C., 15-19 Feb., 1999. Vol. 1; B.C. Minist. Environ., Lands and Parks, Victoria, BC, and Univ. College of the Cariboo, Kamloops, BC. 490pp.

Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2020d. Recovery Strategy for the Sharp-Tailed Snake (Contia tenuis) in Canada. species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment and Climate Change Canada, Ottawa. 2 parts, 17 pp. + 42 pp.

Sharp-Tailed Snake Recovery Team. 2008. Recovery Strategy for the Sharp-Tailed Snake (Contia tenuis) in British Columbia. Prepared for the B.C. Ministry of Environment, Victoria, BC. 27 pp.

https://www.bcreptiles.ca/snakes/sharptail.htm

http://canadianherpetology.ca/species/species_page.html?cname=Common%20Sharp-Tailed%20Snake

http://linnet.geog.ubc.ca/efauna/Atlas/Atlas.aspx?sciname=Contia%20tenuis&ilifeform=42