Credit: Stew Carrington

Northern Alligator Lizard

Elgaria coerulea

Description

The Northern Alligator Lizard is a small, short-legged, long-bodied lizard with a triangular head that resembles a miniature alligator, giving it its name. They grow to a maximum of 20 cm total length, with females being slightly larger than males. Males typically have slightly wider heads than females. The size, colouration, and behaviour of Alligator Lizards makes them very cryptic. They are usually brown with a pale belly, and may have dark blotches or a broad bronze stripe down the middle of the back. They are very secretive animals, and their first defense when threatened is to run and hide. When captured, they may release an unpleasant smelling mix of feces and musk, bite, or autotomizeDefinition:The ability to shed part or all of the tail as a defensive mechanism. Nervous impulses in the tail cause it to twitch for some time, distracting potential predators long enough to allow the animal to escape. their tail. The dropped tail will distract predators allowing the Alligator Lizard to escape. They will eventually regrow the tail, although it usually grows back shorter and fatter than before. The tail of the Alligator Lizard is an important fat reserve, so autotomy is likely a last resort, however, many Alligator Lizards are observed with regenerated tails, suggesting it is likely a successful tactic when threatened.

Listen to the Indigenous words for “lizard” here!

Similar Species

The Common Wall Lizard loosely resembles the Northern Alligator Lizard, although the two are easily distinguished by body shape and colour. The Northern Alligator Lizard has less noticeable patterning, is stouter and shorter, and is far more widespread in British Columbia.

Northern Alligator Lizard

Common Wall Lizard

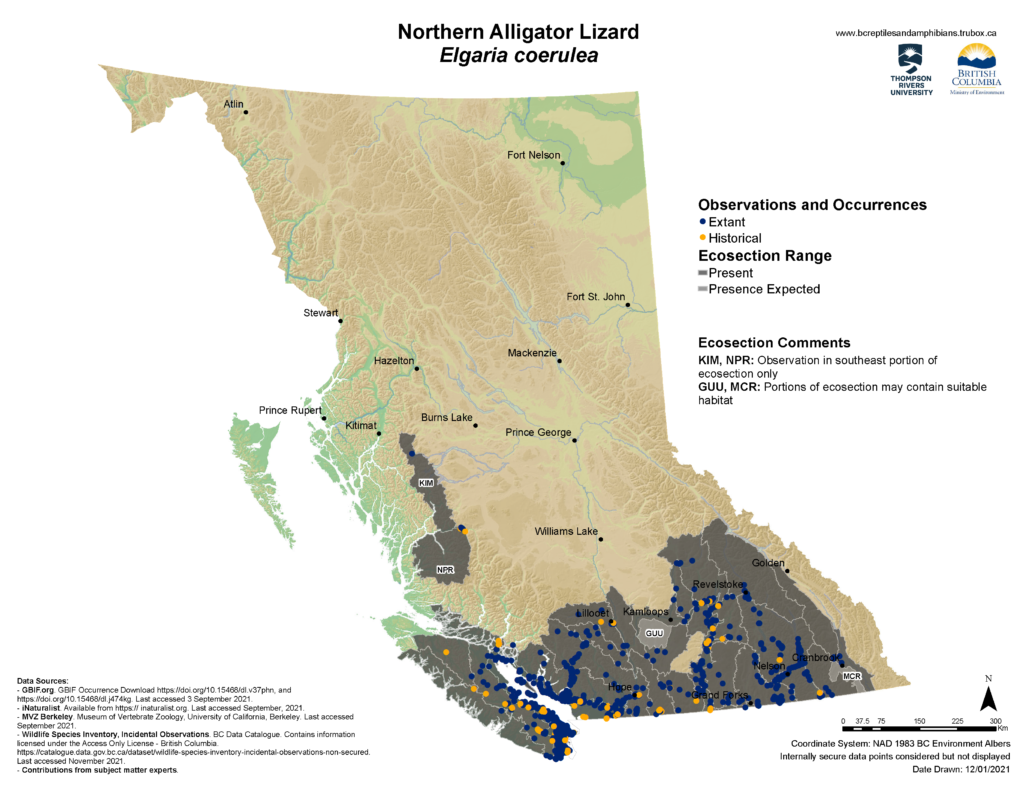

Distribution

Habitat

Northern Alligator Lizards spend the winters hibernating in underground dens. In British Columbia, Alligator Lizards will generally remain very close to their hibernacula year-round. They display a high level of site fidelity, and individuals are regularly recaptured within 10 m of a previous capture, both within a summer season and between seasons. Instances of Alligator Lizards moving more than 100 m from their overwintering sites are rare. Compared to other lizards, Northern Alligator Lizards tolerate cool, wet climates well, allowing them to occupy a diversity of habitats including montane forests, dry woodlands, grasslands, riparian zones, and marine beaches. However, Alligator Lizards seem to prefer Douglas-fir and Hemlock forests where they seek out rocky outcroppings, talus slopes, and streams. Alligator Lizards also do very well in disturbed sites such as logging mills, hydrocuts, and clear-cuts where there is abundant surface debris. Generally, they require a large amount of surrounding vegetation and rocks or debris for cover. Hibernation occurs in rock crevices well below the freezing line. Alligator Lizards may be found in conjunction with Common Wall Lizards and Western Skinks.

Reproduction

Mating begins almost immediately after emergence from the den. Male Alligator Lizards do not make any fancy displays or courtship rituals. Instead, they will simply chase down a female, bite her head to grasp her in his jaws, and begin mating. This may explain why males have larger heads than females. In some cases, mating may last up to twelve hours, leaving the lizards open to danger during the interaction. Alligator Lizards are viviparousDefinition:A reproductive strategy where the mothers both give birth to live young, and provide nourishment for offspring as they develop in the mother’s womb. lizards that carry their young throughout the summer which allows the females to protect the developing young and provide the best possible levels of heat and humidity. Even after birth, parental care has been observed among Alligator Lizards, providing a greater chance of survival for the young. However, this strategy also restricts how much females can eat while providing care and requires them to bask more often, exposing them to predators. Alligator Lizards give birth to an average of 5 young, though this may range from 2 – 8. Females will breed every 2 years on average as they require a year in between clutches to eat, grow, and regain their fat reserves.

Diet

Conservation Status

Global: G5 (2016)

COSEWIC: NAR

Provincial: S4 (2018)

BC List: Yellow

Learn more about conservation status rankings here

Threats

Peripheral populationDefinition:Occur near the outer boundary of the geographic range of the species., such as the Northern Alligator Lizards in British Columbia, are extremely important as they can carry different genes that make them more successful than individuals in populations closer to the centre of their range, contributing to the diversity of the species. Alligator Lizards are likely highly affected by rock removal for road construction or landscaping due to their dependence on, and high fidelity to, rocks as basking sites and over-wintering sites. They are also very easily disturbed and may hide for several hours after encountering a predator (or a curious human). This type of disturbance may be particularly detrimental to pregnant females. While little is known about the size or structure of Northern Alligator Lizard populations in British Columbia, biologists feel that the distribution and resilience of the species is favourable. However, an emerging concern for Northern Alligator Lizards is how competition with European Wall Lizards may impact populations where they overlap, or where new populations of Wall Lizards are introduced. Wall Lizards may outcompete and push out Northern Alligator Lizards which could lead to local declines.

Common Wall Lizard

Did You Know?

Species Account Author: Marcus Atkins

B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2003. Species Summary: Elgaria coerulea. B.C. Minist. of Environment. Available: https://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/ (accessed May 31, 2021).

B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2021. BC Species and Ecosystems Explorer. B.C. Minist. of Environ. Victoria, B.C. Available: https://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/ (accessed May 31, 2021).

COSEWIC. 2002. COSEWIC Status Report on the Northern Alligator Lizard Elgaria in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 32 pp.

https://www.bcreptiles.ca/lizards/alligator.htm

http://linnet.geog.ubc.ca/efauna/Atlas/Atlas.aspx?sciname=Elgaria%20coerulea