Credit: Joe Crowley

Rough-skinned Newt

Taricha granulosa

Description

Other names: Pacific Coast Newt, Roughskin Newt, Western Newt

Listen to the Indigenous words for “salamander” here!

Similar Species

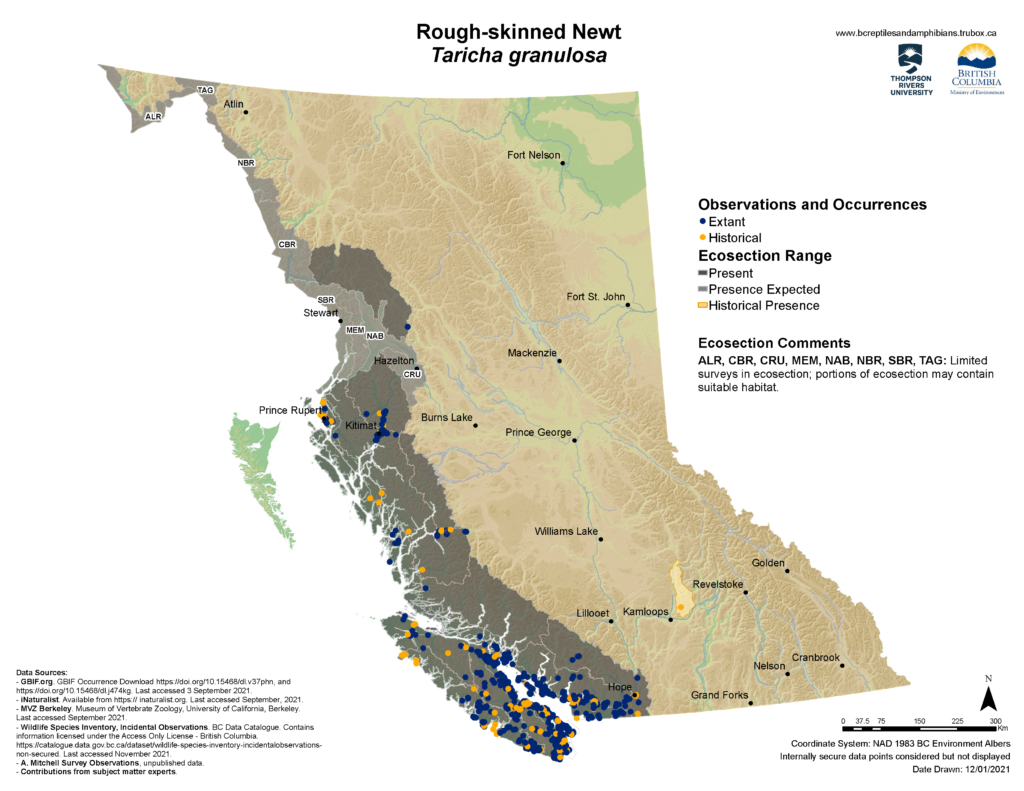

Distribution

Habitat

Reproduction

Rough-skinned Newts spend the majority of the breeding season in aquatic habitats, and terrestrial adults will migrate to these habitats in spring. Breeding generally happens in the spring, although some neotenic adults will breed in the fall. The male will deposit a sperm packet (spermatophore) that the female will pick up with her cloacaDefinition:The common cavity in which the intestinal, urinary, and reproductive canals open in birds, reptiles, amphibians, many fishes, and certain mammals.. Unlike other salamander species, female Rough-skinned Newts lay each egg singly across the breeding habitat, attaching them to vegetation underwater. Eggs hatch after 3-4 weeks, and larvae will metamorphose in late summer or the following year, depending on local conditions. Rough-skinned Newts reach sexual maturity after 4-5 years, and can live over 12 years.

Diet

Conservation Status

Global: G5 (2008)

Provincial: S4S5 (2016)

BC List: Yellow

Learn more about conservation status rankings here

Threats

Did You Know?

The toxin that Rough-skinned Newts create is a tetrodotoxin, similar to that created by pufferfish, and the level of toxicity varies throughout its range. Gartersnakes are one of the main predators of Rough-skinned Newts, and have evolved a resistance to the toxin. In response, Rough-skinned Newt populations that are heavily predated by Gartersnakes develop more potent toxin, leading to an arms-race between the two species. Gartersnakes have been shown to assess their level of resistance to each individual newt, rejecting individuals that taste too ‘poison-y’. Those newts that were rejected by Gartersnakes tend to survive, and pass on their genes, as there are reports of newts being attacked and ingested for over 50 minutes and escaping with their lives.

When threatened, the Rough-skinned Newt will roll over to expose its bright orange belly which serves as a warning signal to predators, as they are the most toxic amphibian in the Pacific Northwest.

Species Account Author: Marcus Atkins

B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2010. Species Summary: Taricha granulosa. B.C. Minist. of Environment. Available: https://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/ (accessed Jun 7, 2021).

B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2016. Conservation Status Report: Taricha granulosa. B.C. Minist. of Environment. Available: https://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/ (accessed Jun 7, 2021).

B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2021. BC Species and Ecosystems Explorer. B.C. Minist. of Environ. Victoria, B.C. Available: https://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/ (accessed Jun 7, 2021).

Matsuda, Brent M., David M. Green and Patrick T. Gregory. 2006. Amphibians and Reptiles of British Columbia. Royal BC Museum Handbook. Victoria.

http://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eirs/finishDownloadDocument.do?subdocumentId=7962

http://www.canadianherpetology.ca/species/species_page.html?cname=Rough-skinned%20Newt

https://linnet.geog.ubc.ca/efauna/Atlas/Atlas.aspx?sciname=Taricha%20granulosa