Credit: Jade Spruyt

Western Tiger Salamander

Ambystoma mavortium

Description

Other names: Ambystoma tigrinum, Blotched Tiger Salamander, Barred Tiger Salamander, Tiger Salamander

Tiger Salamanders are members of the family Ambystomatidae, also known as the mole salamanders. This family is native to North America and are characterized by distinct costal groovesDefinition:Grooves along the sides of a salamander’s body that increase the surface area of the skin and creates channels for water to flow and collect on their body. This is important to prevent their skin from drying out. and laterally compressed tails. Tiger Salamanders are the largest terrestrial salamanders after the Giant Salamanders, and are only active at night. In British Columbia, the Western Tiger Salamander can grow to over 30 cm in total length, although most individuals are between 15-20 cm. They have a robust body with 12-14 costal grooves, a broad head with small eyes, and a laterally compressed tail that is especially obvious in males. Tiger Salamander colouration shifts with age, with young individuals displaying light yellow or cream blotches or bars on a dark background, that changes to dark bars or blotches on a light background. Western Tiger Salamanders may also persist in neotenicDefinition:The retention of juvenile characteristics in an adult. In amphibians, particularly amongst salamanders, neotenic individuals mature to a reproductive stage without fully undergoing the process of metamorphosis from aquatic larva to land-based adult. forms, and can grow larger than terrestrial adults. Neotenic individuals are olive to greenish yellow with both front and back legs, a tail fin, and feathery gills.

Listen to the Indigenous words for “salamander” here!

Similar Species

In B.C., the Western Tiger Salamander may be confused with the Northwestern Salamander or the Coastal Giant Salamander, although their ranges do not overlap. No other species of salamander in the range of the Coastal Giant grows quite as large and has a marbled brown or gold patterning. The Northwestern Salamander also grows quite large, but has parotid glandsDefinition:An external skin gland on the back, neck, and/or shoulder of some toads, frogs, and salamanders, usually visible as a bump. It can secrete a number of milky alkaloid substances which help deter predators., and is usually a uniform dark colour.

Western Tiger Salamander

Northwestern Salamander

Coastal Giant Salamander

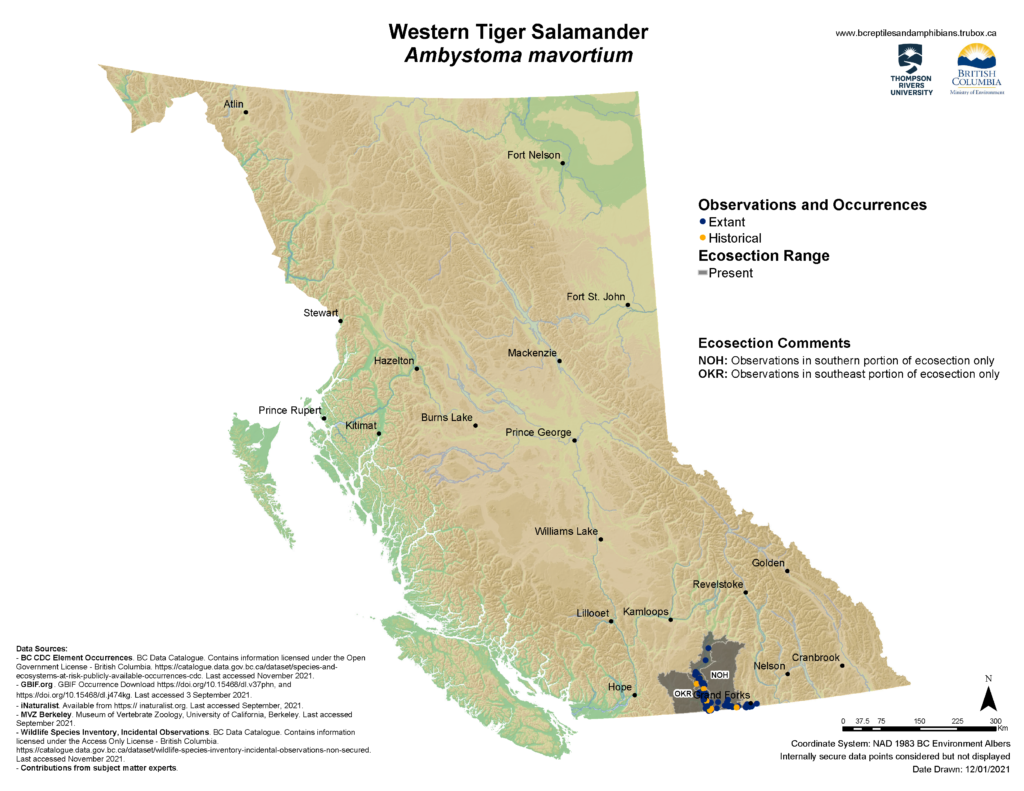

Distribution

Habitat

Adult Western Tiger Salamanders may be either terrestrial or aquatic (neotenic). NeotenicDefinition:The retention of juvenile characteristics in an adult. In amphibians, particularly amongst salamanders, neotenic individuals mature to a reproductive stage without fully undergoing the process of metamorphosis from aquatic larva to land-based adult. adults will only persist in permanent water bodies devoid of fish. Terrestrial adults spend most of their lives underground, using their forelimbs to burrow into soft and malleable soils. Western Tiger Salamanders are associated with Ponderosa Pine, Bluebunch Wheatgrass, and Douglas-Fir ecosystems. Terrestrial adults are found close to ponds and small lakes and may take shelter in small animal burrows or beneath coarse woody debris in damp areas. Tiger Salamanders are most often spotted at night during the spring breeding season, especially during rain events. In the summer months, adults will hunker down in burrows to escape hot and dry conditions. Tiger Salamanders will overwinter underground below the frost line either in burrows they excavate themselves, or old mammal burrows. In British Columbia, there is a positive association of Tiger Salamanders with Pocket Gophers, as old burrows provide easy access to subterranean (underground) habitat.

Reproduction

Diet

Conservation Status

Global: G5 (2016)

COSEWIC: E

SARA:1-E (2018)

Provincial: S2 (2016)

BC List: Red

Learn more about conservation status rankings here

Threats

Did You Know?

Species Account Author: Marcus Atkins

B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2010. Species Summary: Ambystoma mavortium. B.C. Minist. of Environment. Available: https://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/ (accessed Jun 2, 2021).

B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2016. Conservation Status Report: Ambystoma mavortium. B.C. Minist. of Environment. Available: https://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/ (accessed Jun 2, 2021).

B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2021. BC Species and Ecosystems Explorer. B.C. Minist. of Environ. Victoria, B.C. Available: https://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/ (accessed Jun 2, 2021).

COSEWIC. 2012g. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Western Tiger Salamander Ambystoma mavortium in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xv + 63 pp.

Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2017x. Recovery Strategy for the Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment and Climate Change Canada, Ottawa. 2 parts, 19 pp. + 39 pp.

Southern Interior Reptile and Amphibian Working Group. 2016. Recovery plan for the Western Tiger Salamander (Ambystoma mavortium) in British Columbia. Prepared for the B.C. Ministry of Environment, Victoria, BC. 39 pp.

http://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eirs/viewDocumentDetail.do?fromStatic=true&repository=BDP&documentId=10520

http://linnet.geog.ubc.ca/efauna/Atlas/Atlas.aspx?sciname=Ambystoma%20mavortium

http://canadianherpetology.ca/species/species_page.html?cname=Western%20Tiger%20Salamander