Credit: J. Maughn

Western Skink

Plestiodon skiltonianus

Description

Other names: Eumeces skiltonianus

The Western Skink is a long-bodied lizard with short legs and a long, narrow, pointed head. They are a small lizard, with most individuals reaching body lengths of 10 cm, although their tails may reach up to 12 cm for a total length of over 20 cm. Western Skinks are most brilliantly coloured as juveniles. They have smooth, shiny scales and are brown on the back with gray sides that contrast 4 cream-white stripes that run from the head to their brilliant bright blue tail. As Western Skinks age their colours tend to fade. During the breeding season males develop reddish patches on the chin and on the sides of the head. When threatened, Western Skinks will attempt to escape by wiggling under a rock or nearby shrub with a snake-like body movement. However, if they are captured by a predator, they will autotomizeDefinition:The ability to shed part or all of the tail as a defensive mechanism. Nervous impulses in the tail cause it to twitch for some time, distracting potential predators long enough to allow the animal to escape. their tail. When dropped, the bright blue tail continues to thrash and twitch for a period of time, providing a distraction for the tailless skink to escape to safety. Western Skinks will regrow their tail when lost as big or bigger than before, but it rarely returns to the original brilliant blue when regrown.

Listen to the Indigenous words for “lizard” here!

Similar Species

The Western Skink is a colourful lizard with a body form that resembles the comparatively drab Northern Alligator Lizard.

Western Skink

Northern Alligator Lizard

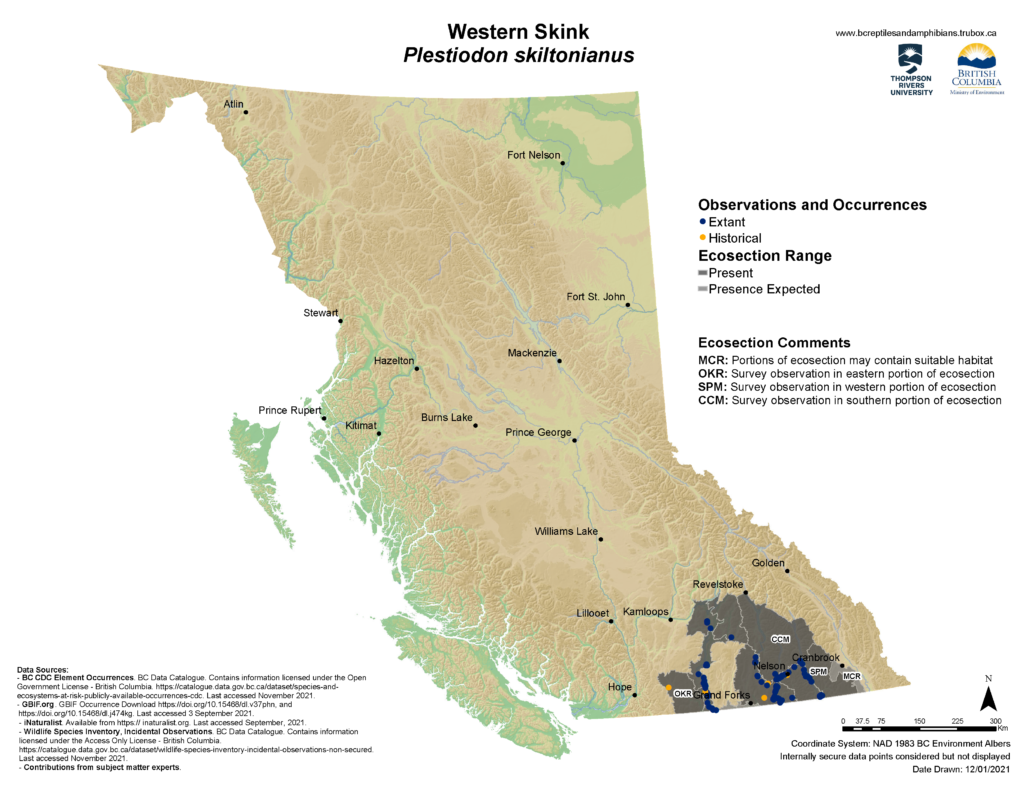

Distribution

Habitat

Western Skinks are found in many of the same habitats as the Northern Alligator Lizard, including Bunchgrass, Ponderosa Pine, Interior Douglas-fir, and sometimes in Engelmann Spruce – Subalpine Fir and Cedar-Hemlock ecosystems. They require plenty of plant cover and rocks, logs, stumps, and bark for cover and foraging, sunny clearings for basking, and south facing slopes and rocks for nesting and denning. In British Columbia, Western Skinks hibernate throughout the winter and are active from mid-April until October. They hibernate in communal hibernaculaDefinition:Winter dwelling of a hibernating animal. and may share dens with Northern Alligator Lizards, Rubber Boas, and possibly even Western Rattlesnakes. In parts of British Columbia, Western Skinks do not appear to migrate from their summer habitat for hibernation and generally mate and feed very close to the den. Further south in the United States, migration from hibernation sites to summer habitats has been reported. Western Skinks return to the same sites year after year with high fidelity and are often caught within 10m of their previous capture. Movements of more than 100 m are very rare.

Reproduction

The breeding season for the Western Skink begins in spring, almost immediately after they emerge from their dens. Western Skinks are oviparousDefinition:A reproductive strategy where the female lays eggs that develop outside of the mother’s body.. Mating takes place in April-May, egg-laying occurs in June and July, and hatching occurs in August or early September. Female Western Skinks will make a nest for their eggs by digging a small burrow under rocks or other cover objects. Western Skink mothers will stay with their eggs until they hatch, aggressively guarding them. This form of parental care (defense of eggs) is uncommon among lizards.

Diet

Western Skinks hunt during the day by stalking their prey with intense focus and speed. Food consumption in nature is not well understood, but Western Skinks appear to be mainly invertivoresDefinition:Feeding on invertebrates. dining on caterpillars, moths, beetles, grasshoppers, spiders, isopods, and crickets.

Conservation Status

Global: G5 (2016)

COSEWIC: SC

SARA:1-SC (2005)

Provincial: S3S4 (2018)

BC List: Blue

Learn more about conservation status rankings here

Threats

Did You Know?

If a Western Skink loses its beautiful blue tail, it will grow back but will very rarely keep its brilliant blue.

Species Account Author: Marcus Atkins

B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2005. Species Summary: Plestiodon skiltonianus. B.C. Minist. of Environment. Available: https://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/ (accessed May 28, 2021).

B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2021. BC Species and Ecosystems Explorer. B.C. Minist. of Environ. Victoria, B.C. Available: https://a100.gov.bc.ca/pub/eswp/ (accessed May 28, 2021).

COSEWIC. 2014i. COSEWIC status appraisal summary on the Western Skink Plestiodon skiltonianus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xvi pp.

Environment Canada. 2015n. Management Plan for the Western Skink (Plestiodon skiltonianus) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Management Plan Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. 4 p. + Annex.

https://www.bcreptiles.ca/lizards/westskink.htm

http://linnet.geog.ubc.ca/efauna/Atlas/Atlas.aspx?sciname=Plestiodon%20skiltonianus